Faceless Men and Fuckable Dolls: On Who Desire Really Serves

You can be sexy, just don’t scare the men

I. Introduction – The Illusion of Sexual Empowerment

Let’s set the scene—you’re on the internet browsing through the latest iteration of cultural discourse where a young, white starlet ignites a wildfire of outrage. Whether it be actress Sydney Sweeney wearing a low-cut dress or launching a line of soap made from her bathwater. Or pop star Sabrina Carpenter posing provocatively for her latest album, play-acting sexual submission and referring to herself as “Man’s Best Friend.”

Each time the internet explodes, and each time we get the same tepid defences. She’s reclaiming her power. She’s owning her sexuality. She’s being sexy for herself. Those who don’t see it are quickly cast as jealous prudes, unfuckable femcels, or threatened by female sexuality.

I have already written extensively on how the women who challenge male power or push back against dominant patriarchal narratives tend to be disparaged with gendered, ad hominem attacks.

To be clear, I am neither prudish nor threatened, and I certainly don’t consider the kind of sexuality on display by either woman worthy of envy. I recognise that leaves me wide open to the accusation of being an “unfuckable, ugly femcel” to which I say, you are more than welcome to call me that—so long as you acknowledge I am neither stupid nor wrong :).

Now that’s out of the way, we can get to the crux of the article: asking the question of who this display of sexuality is ultimately for, and what rules govern its “acceptability”.

And can something truly be subversive when it already panders to the most blandly accepted social scripts?

II. The Faceless Man: A Canvas for Projection

There have been many takes regarding Sabrina Carpenter’s most recent rollout—much of them sharp, incisive, and deeply valid. But none quite hit the mark for why this photoshoot in particular happened to niggle at me. And, to be clear, this isn’t reserved for Carpenter alone. Pop culture has a long legacy of peddling this exact carbon copy of Monroe-esque bombshells since the progenitor of the archetype herself.

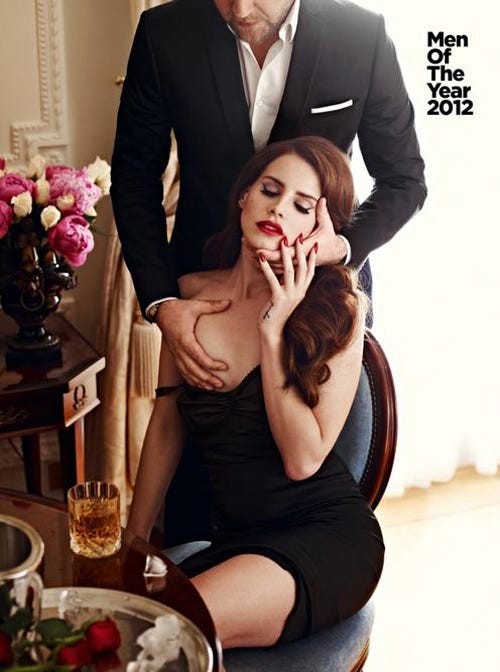

For decades, we’ve been churning out a conveyor belt of perky, plucked, and perfect women in high-gloss visuals, vintage filters, wearing babydoll dresses with sky-high heels, face directed coyly towards the camera ready to please—and always, always a faceless male body nearby.

We might see his hands. Maybe a well-tailored suit. Occasionally a stubbled jawline. But never his face. Never any identifying features. Never his personhood. He exists solely as a placeholder, an accessory. A blank slate for projection.

That’s not a coincidence.

The faceless man is a staple of this kind of marketing because it’s not actually about him. It’s about them—the audience of male viewers meant to see themselves in his place. The implication is clear:

“You could be the one she sings about. You could be the one she begs for.”

The woman, meanwhile, is hyper-legible. You can see everything: her face, her hair, her pout, the curve of her waist, the arch of her back. She is the image. She is the fantasy. She is what’s for sale.

And we’re supposed to call this empowerment.

But let’s be real. That’s not sexual liberation. That’s pandering dressed up in silk stockings and lip gloss. That’s submission, sanded down to be palatable—marketable—to the same men who’d call a woman a slut for doing the exact same thing if it wasn’t pretty, playful, and designed with their gaze in mind.

This isn’t about being against sexual expression. It’s about recognising that not all desire is structured the same way. A lot of what gets pushed as “female sexuality” in pop culture is just male fantasy in drag. Women are allowed to express desire, sure—but only if it’s vague, non-threatening, and ultimately reaffirms men’s desirability.

III. Performative Submissiveness vs Actual Female Desire

See, real female desire, the kind that unsettles, often involves taste. Preference. Discrimination. The ability to look at a man and say, “Not you.” That’s dangerous. That’s ego-bruising. And that’s why we rarely see it onscreen.

Ironically, it’s often the romance book genre that leads the charge on this. With it often and regularly coming under fire by external critics for “setting unrealistic standards for men.”

Compare and contrast the social media outcry when Tinder announced the soft-launch of a height filter that would allow premium users to select how tall their potential matches would be. Men across Twitter, Reddit, and Instagram had a collective meltdown when they feared it would make their already scarce matches that much more limited.

Many of them called for a retaliative “weight filter” for women, where they could set potential matches to weigh “under 200 pounds”. The problem with this is women already grow up with an intimate knowledge of how our various flaws and defects might deselect us from a man’s prospective dating pool. That’s part of the issue.

So many of us have been mentally terrorised by the fear of inadequacy—of never being chosen—that we developed this disembodied, voyeuristic lens with our own sexuality as a defence mechanism. Now, it doesn’t have to be about what we want from a man, but whether he wants us. We don’t have to think about whether or not we are truly, deeply attracted to him, or if he fits into our desires and preferences—so long as he wants us badly enough and has the courage to pursue it.

The farce behind shoots like Sabrina Carpenter’s is it peddles female desire but refuses specificity. The idea that the submissive sexual fantasy she longs for could not be fulfilled by any man but a man in particular. One that might be fitting of a certain rugged, powerful masculinity that many men deeply long to embody but keep falling short of.

Thus, we cut the man out of the frame. Not to centre her focus, but to lessen his. To quell the underlying panic that pulses through these men before they reach for themselves under the desk—that he might not be her choice.

IV. White Femininity and the Marketable Gaze

What doesn’t get touched on enough is this imagery is not inherently neutral.

There’s a certain kind of sexuality that gets lauded in the public eye and celebrated as “empowering”, and it often aligns with white supremacist beauty ideals: thin, pale, youthful, and non-confrontational. Pop stars like Carpenter are allowed to play coy and submissive with it not hurting their perception of femininity, delicacy, and romantic desirability.

Meanwhile Black stars like Glorilla and Megan Thee Stallion are often derided for the same sexual explicitness as vulgar, crass, and low-class—proof of the hypersexual Jezebel stereotype that gets regularly foisted on us. Even positive perceptions of Meg focus more on her “powerfulness” and prowess.

We’re good enough for bed, but not good enough to wed.

For this reason, many Black women, myself included, can feel further maligned rather than represented by Carpenter’s merging of the 50s white pin-up with the modern pornstar fantasy. Because in neither of those ideals will we find our reflection. It was never intended for us at all.

As the West continues to descend into far-right populism, it is our responsibility as women to remain vigilant for this kind of insidious propaganda in our media. We are currently seeing a worrying rise of female youth falling for fascistic ideals and conservative gender roles: “clean girl”, “tradwife”, “I’m just a girl”, “bimboification”, and the widespread popularisation of harmful diet drugs like ozempic.

Artistic choices like Sabrina Carpenter’s cannot be dismissed under empty platitudes such as “let women enjoy things” in such a cultural climate. It sends a message. It draws a line. And it sets a dangerous precedent for what side Carpenter has chosen in this fight, whether she acknowledges it or not.

V. Conclusion – You’re Not Wrong for Feeling Alienated

So no, I refuse the idea that every risque photoshoot is a feminist act. Especially not when it’s clearly designed to be just transgressive enough to get attention, but not so transgressive that it alienates men. This is not liberation. This is performance. This is strategy.

And it’s okay to say: “This doesn’t represent me.”

Because not everyone expresses desire by being looked at. Some of us express it by looking back. Some of us want to choose, not just be chosen. And some of us are tired of watching the same striptease played out in pop culture under the guise of empowerment—when it’s really just another reminder that women are allowed to be sexual, but only if it turns the man on.

You can keep the faceless man. I want one who’s fully visible—and visibly chosen by me.

If this piece resonates with you, please consider donating to me on ko-fi. It helps me continue what I do.

If you have thoughts, critiques, and areas you’d like to discuss further, feel free to leave a comment!

I’d love to hear from you.

Straight to the heart of the matter, as always!! (Yeesh, that photo of Lana Del Rey makes my skin crawl.)

"Because not everyone expresses desire by being looked at. Some of us express it by looking back. Some of us want to choose, not just be chosen. And some of us are tired of watching the same striptease played out in pop culture under the guise of empowerment—when it’s really just another reminder that women are allowed to be sexual, but only if it turns the man on." Well-said!!